ECW CTF 2021: Pipe Dream (Writeup)

From October 8th to October 24th took place the online qualification round for the European Cyber Week CTF Finals, that are held every year in Rennes, France.

I had the opportunity to create a challenge for this event as part of my internship at Thalium. This was the first time I actually publish a challenge and I hope those who gave it a try enjoyed it.

This writeup is of course not meant to convey the perspective of a player, but rather aims to be an explanation of the task and my thoughts as its author.

- Getting started

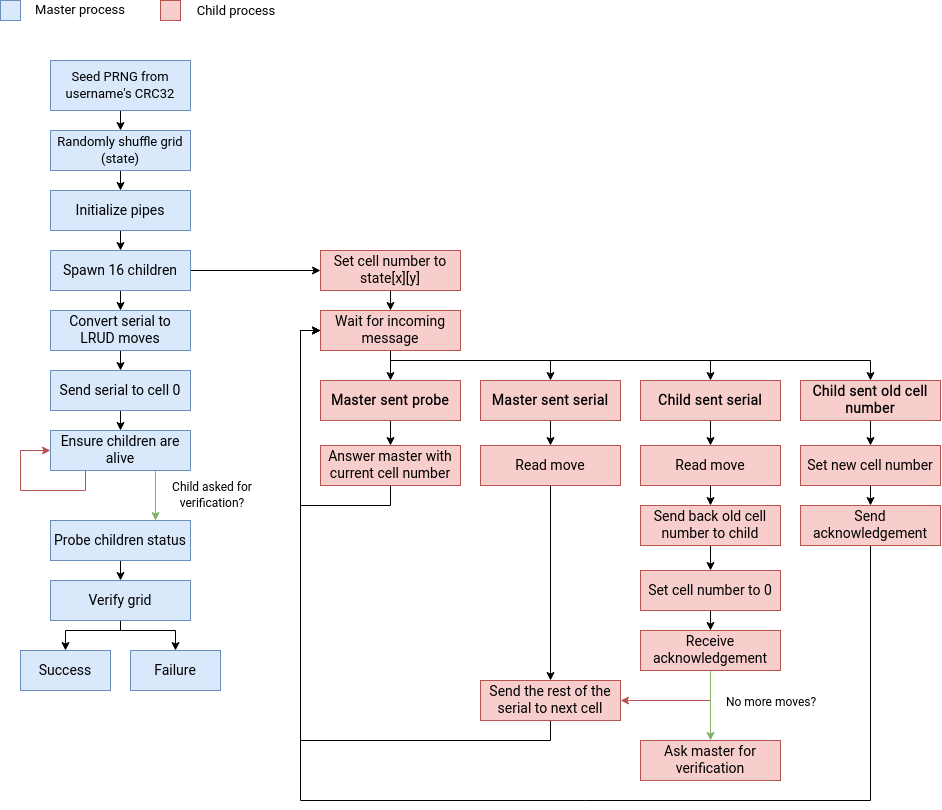

- Understanding the big picture

- Reversing the protocol

- Puzzle state machine

- Writing a keygen

- Against the remote

- Conclusion

- Full source code

Getting started

Pipe Dream is a classic Linux x86 reverse engineering challenge on the medium-harder side of the difficulty spectrum. It was solved by only one contestant (at least officially), making it the least solved reverse challenge of the event, and the least solved challenge overall.

You can download it here: pipedream.

A group of hackers have taken over our hospital. They installed a backdoor; we have located it, but it has an authentication system. Help us defeat their system!

This binary asks for a username and a serial key. Implement a keygen and try it online (through VPN) at

tcp://10.4.0.12:42000

From the description, we learn that we got our hands on a keygen crackme. The online validation service will probably ask us to generate valid keys for given usernames or something.

Let’s run the binary and see what it’s about:

$ ./pipedream

Enter username: abc

Enter serial: def

Not even close. Bye!

[1] 14830 killed ./pipedream

The binary does not seem to exit the normal way… It seems like a process has been killed by one another.

$ ./pipedream

Enter username: abc

Enter serial: ABCD

You lost your path and fell into lava. It hurts and you die.

I lost my child :(

[1] 14998 killed ./pipedream

$ ./pipedream

Enter username: abc

Enter serial: 00

You lost your path already?

I lost my child :(

[1] 15309 killed ./pipedream

Okay, what the heck? Without further ado, let’s fire up IDA.

The binary does not seem obfuscated and the code looks relatively nice; it was probably written in C. We immediately locate the main function (sub_343D) that, among other things, asks for user input.

v6 = 0;

v14[0] = 0x706050403020100LL;

v14[1] = 0xF0E0D0C0B0A0908LL;

printf("Enter username: ");

__isoc99_scanf("%511s", username);

v4 = strlen(username);

sub_1477(username, v4, &v6);

sub_1418(v6);

sub_1660(v14, 16LL);

sub_16EA();

Many functions are called after we input our username.

sub_1477: we can recognize it computes a CRC32, which we can verify dynamically. It does not use a fast lookup table, but we can notice the use of the polynomial0xEDB88320.sub_1418only takes the CRC sum and puts it in a static global variable (dword_6010).

If we look for other references to this DWORD, we can see it is used in sub_13E4 which is a mere linear congruential generator (dword_6010 = 1103515245 * dword_6010 + 12345). Therefore, sub_13E4 must be some kind of rand function, and sub_1418 an srand function.

The next function, sub_1660, takes v14 and considers it as a 16-byte array (0, 1, ..., 15). It then performs severals swaps between randomly generated indexes. One can recognize a Fisher-Yates shuffle, which outputs here a random permutation of the integers between 0 and 15.

The fun starts inside the sub_16EA function.

unsigned __int64 sub_16EA() {

int i; // [rsp+Ch] [rbp-24h]

int j; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-20h]

int k; // [rsp+14h] [rbp-1Ch]

int l; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-18h]

int m; // [rsp+1Ch] [rbp-14h]

int pipedes[2]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-10h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v7; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-8h]

v7 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

for ( i = 0; i <= 3; ++i ) {

for ( j = 0; j <= 3; ++j ) {

for ( k = 0; k <= 3; ++k ) {

for ( l = 0; l <= 3; ++l ) {

if ( i == k && abs32(j - l) == 1 || j == l && abs32(i - k) == 1 ) {

if ( pipe(pipedes) ) {

puts("pipe failed");

exit(-1);

}

dword_6060[64 * i + 16 * j + 4 * k + l] = pipedes[0];

dword_6460[64 * i + 16 * j + 4 * k + l] = pipedes[1];

}

}

}

for ( m = 0; m <= 1; ++m ) {

if ( pipe(pipedes) ) {

puts("pipe failed");

exit(-1);

}

dword_6860[16 * m + 4 * i + j] = pipedes[0];

dword_68E0[16 * m + 4 * i + j] = pipedes[1];

}

}

}

return v7 - __readfsqword(0x28u);

}

This function creates a bunch of pipes when certain conditions are met, and puts the pipes’ file descriptors inside several arrays.

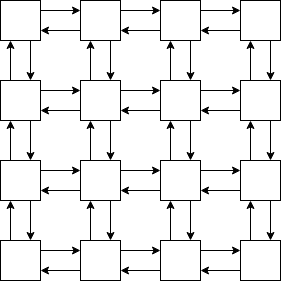

The condition $((i = k) \land (\lvert j - l \rvert = 1)) \lor ((j = l) \land (\lvert i - k \rvert = 1))$ gives out a big clue. $(i, j)$ and $(k, l)$ probably represent coordinates on a $4 \times 4$ grid, and the condition checks whether two cells are adjacent.

dword_6060 and dword_6460 are both global arrays of length 256, indexed by $64i + 16j + 4k + l$, a base 4 decomposition to identify the couple of cells $(i, j), (k, l)$. The first array receives the read end of the pipe, and the second array receives the write end.

By symmetry, a pipe is also created for the $(k, l), (i, j)$ couple. A potential intuition at this point is that each cell has a pipe’s read end and a pipe’s write end linked with all of its adjacent cells. In other words, each cell can read from an adjacent cell and write to an adjacent cell; they can communicate in some bi-directional way.

There are also two other global arrays, dword_6860 and dword_68E0, of length 32. These store the read and write ends of two pipes associated with a cell $(i, j)$. We’re not sure what this means yet…

For now, we will rename the four aforementioned arrays $P$, $Q$, $R$ and $S$. We will also rename sub_16EA as init_pipes.

Understanding the big picture

Let’s come back to the main function. After using our username to generate a permutation and initializing all these pipes, the binary starts madly forking itself:

for ( i = 0; i <= 3; ++i )

{

for ( j = 0; j <= 3; ++j )

{

v7 = fork();

if ( v7 == -1 )

{

puts("fork failed");

exit(-1);

}

if ( !v7 )

goto LABEL_10;

}

}

LABEL_10:

// ...

In fact, the master process will fork and spawn 16 children processes.

How convenient… What if our little cells from earlier are actually these processes, and they use pipes to communicate?

The rest of the main function depends on whether we’re a child process or the master process. If we’re a child process:

- We put

random_permutation[4 * i + j]inside the static global variablebyte_6044, which we will renamecell_number. - We call

sub_2080(i, j). Since this function’s logic is wrapped inside an infinite loop, we’ll rename itchild_loop.

Before diving any further in what the child processes do exactly, let’s reverse the master process.

It starts by using setsid and getpgid to ensure it is the process group leader, and get the process group id, which should be its own PID. Indeed, in Linux, processes have a Process ID (PID), a Parent Process ID (PPID), and can also have a Process Group ID (PGID). If a process’ PGID is its PID, then it is a process group leader.

Here, all the child processes belong to the same group. This allows, for instance, to kill all children at once with killpg (in sub_1388).

Then, the master process finally reads the serial from standard input. The serial goes through sub_1530, where it is converted from uppercase hexadecimal to base 4. The resulting array is a sequence of integers from $1$ to $4$. For example, the serial AB42 would be converted to $(3, 3, 3, 4, 2, 1, 1, 3)$.

Next, the random permutation of $\{0, \ldots, 15\}$ is seen as a $4 \times 4$ grid, and the master process loops until it finds the coordinates $(k, l)$ of $0$ inside the grid. Then, it calls sub_1A90 with S[4 * k + l] and the converted serial. Remember S[4 * k + l] was the writing end of a pipe associated with the cell $(k, l)$. This function is relatively simple:

ssize_t __fastcall sub_1A90(int pipe_writing_end, const void *serial, unsigned int serial_length)

{

char *buf; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-10h]

ssize_t v6; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-8h]

buf = (char *)malloc(serial_length + 3);

*buf = 'S';

*(_WORD *)(buf + 1) = serial_length;

memcpy(buf + 3, serial, serial_length);

v6 = write(pipe_writing_end, buf, serial_length + 3);

free(buf);

return v6;

}

It seems like it is an important function, as there are some other references to it elsewhere in the binary. It writes a buffer to the pipe, composed of:

- The character

'S'(a header? a type?) - The converted serial length (2 bytes)

- The converted serial

Looks like a TLV encoding (type, length, value) for a protocol of some kind. Perhaps cells communicate to each other using some custom protocol? Let’s rename it send_serial for now.

After writing the serial to a pipe associated to the cell $(k, l)$ which is itself associated to the cell number $0$, the master process enters its own loop, master_loop.

Since we’re trying to follow what happens in this binary in some “time linear” fashion, let’s assume one of the child processes will actually read the serial that was just written and start reversing the child loop.

The child loop is somewhat denser that the other functions, so I will try to cut to the interesting bits. The infinite loop starts with:

v21 = &readfds;

for ( i = 0; i <= 0xF; ++i )

v21->fds_bits[i] = 0LL;

IDA helps a lot here by recognizing an fd_set structure. It is usually used with the select / pselect functions. Those allow to monitor multiple file descriptors at the same time. Can you see where this is going?

Along with select come very handy macros such as FD_ZERO (the loop above which sets the fds_bits to zero), FD_ISSET and FD_SET, which we encounter a few lines below:

for (j = -1; j <= 1; ++j) {

for (k = -1; k <= 1; ++k) {

if ( (!j || !k) && (j || k) && j + a1 >= 0 && j + a1 <= 3 && k + a2 >= 0 && k + a2 <= 3 ) {

v2 = (int)P[64 * j + 64 * a1 + 16 * k + 16 * a2 + 4 * a1 + a2] / 64;

v3 = (int)P[64 * j + 64 * a1 + 16 * k + 16 * a2 + 4 * a1 + a2];

readfds.fds_bits[v2] |= 1LL << ((((HIDWORD(v3) >> 26) + v3) & 0x3F) - (HIDWORD(v3) >> 26));

if ( v17 < (int)P[64 * j + 64 * a1 + 16 * k + 16 * a2 + 4 * a1 + a2] )

v17 = P[64 * j + 64 * a1 + 16 * k + 16 * a2 + 4 * a1 + a2];

}

}

}

For reference, a1 and a2 are the coordinates of the cell associated to the current child process.

Here, the three hideous lines with v2 and v3 can actually be rewritten as:

FD_SET(P[64 * (a1 + j) + 16 * (a2 + k) + 4 * a1 + a2], &readfds);

The FD_SET macro is used to add a file descriptor to the set of file descriptors to monitor. Therefore, the child process is basically saying it wants to monitor the reading ends of the pipes linked to all of its neighbours.

A last file descriptor is also added to the set:

FD_SET(R[16 * 0 + 4 * a1 + a2], &readfds);

Since we know the $S$ array of file descriptors was used by the master process to write data, it may be safe to assume the $R$ array is used by the child processes to read data that was sent by the master process.

There’s even more: remember at the beginning, the master process looked for the coordinates of the $0$ cell in the random permutation and wrote the serial to a pipe associated to these coordinates. This (probably) means two things:

- each process is associated to a cell and can be identified by its coordinates on a $4 \times 4$ grid;

- each process is associated to a cell number according to the initial random permutation (remember the

cell_numberglobal variable? it has a different value for each child process!)

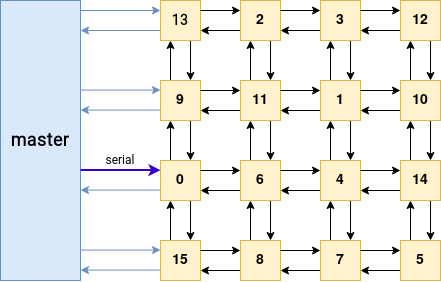

At this point and with our different assumptions, we can break down the architecture this way:

The black arrows represent the $P$ and $Q$ arrays of pipes between child processes, whereas the blue arrows represent the $R$ and $S$ arrays of pipes that allow communication between each child and the master process. Of course, the master process is linked with every child process, but the diagram would have been too cluttered if I were to draw all the pipes.

The first interaction happens when the master process sends the serial to the process whose cell number is $0$. Now what happens next? Let’s continue reversing the child loop to find out.

The select function is finally called with readfds, the set of file descriptors to be monitored. For instance, in the above diagram, the cell $0$ monitors the reading ends of the pipes coming from the cells $9$, $6$ and $15$, as well as the one coming from the master process.

There are three kinds of values that select can return:

- $-1$ if there has been an unexpected error within

select; - $0$ if there hasn’t been any update within a certain timeout duration (30 seconds here);

- the number of file descriptors where something interesting happened otherwise.

Then, we have again some kind of nasty magic operating:

v7 = (int)R[4 * a1 + a2];

if ( (readfds.fds_bits[(int)R[4 * a1 + a2] / 64] & (1LL << ((((HIDWORD(v7) >> 26) + v7) & 0x3F) - (HIDWORD(v7) >> 26)))) == 0 )

break;

This can be rewritten using the FD_ISSET macro:

if (!FD_ISSET(R[16 * 0 + 4 * a1 + a2], &readfds))

break;

FD_ISSET checks if a file descriptor is “ready” for use — here, for reading. If R[16 * 0 + 4 * a1 + a2] is set, this means the master process has sent something to the child process by writing to the corresponding $S$ pipe. If it’s not set, then we know the set file descriptor is a pipe linked with an adjacent child cell.

In the latter case, the child process loops to find which adjacent cell actually sent something. It then proceeds to call sub_19B4 with the file descriptor of interest. This function does not do much: it merely reads one byte from the file descriptor, and returns it.

Depending on the value of this byte:

- If it’s a

'C', the child process reads another byte, does stuff and seems to send something back to the adjacent cell on the reverse pipe… - If it’s an

'S', the child process reads a length, then something of that length, and then… a lot of stuff happens…

It’s starting to get a bit fuzzy, so let’s try to take a step back. We will overlook the protocol for now, and directly skip to the end, which is: how do we reach success?

If we look for strings in the binary, an interesting one stands out: "That's pretty good!". It’s referenced in the master loop: it seems that upon reception of a certain message, a verification of some sort happens:

unsigned char state[16];

memset(state, 0, 16);

sub_1D05(state);

for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++) {

for (int l = 0; l < 4; l++) {

if (state[4 * k + l] != 4 * k + l) {

goto bad_boy;

}

}

}

printf("That's pretty good!\n");

kill_children();

exit(0);

bad_boy:

printf("You failed really hard. At least you managed to survive...\n");

kill_children();

exit(1);

The sub_1D05 function seems to send a certain message to each child process, and wait for a response, which is put in state. It is also probably used to poll on the child processes to check whether they’re still alive or not (hence the "I lost my child :(" that we usually get when we run the binary).

We may assume sub_1D05 asks each cell for their cell number. The constructed state array is then compared to $(0, \ldots, 15)$. This is the condition on which we win.

Since the state was initially a random permutation of $\{ 0, \ldots, 15 \}$, we may also assume there is, somewhere, a mechanism that changes the cells’ numbers (based on the serial?).

From now there are two possibilities.

- Follow your intuition and manage to guess what this is all about…

- …or start reversing the protocol.

Of course, for the sake of this article’s completeness, we will opt for the latter!

Reversing the protocol

This writeup would be too long if I were to detail the entire reversing process, so in this part I will just explain the protocol used by the pipes.

All the messages follow this structure:

[msgType (1 byte)] + [body]

The different message types are the following. We will go through each one in depth.

| msgType | Description | Use cases |

|---|---|---|

'S' | Send serial | Child -> Child, Master -> Child (at the beginning) |

'P' | Probe child status | Master -> Child |

'R' | Probe response | Child -> Master |

'C' | Send old cell number | Child -> Child |

'A' | Acknowledge | Child -> Child |

'V' | Ask master for verification | Child -> Master |

Send serial

[msgType (1 byte)] + [serialLength (2 bytes)] + [serial]

msgTypemust be'S'serialLengthis the length ofserial(little-endian)serialshould not be null terminated

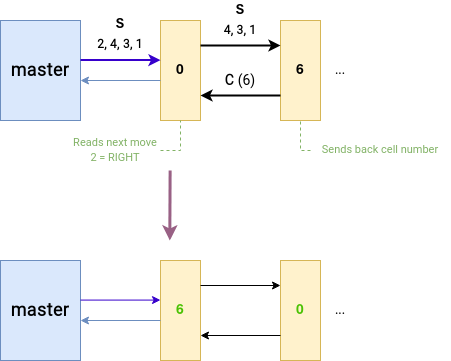

This message is used by the master process to send the entire serial to the first cell ($0$), or by a child process to send the remaining serial to an adjacent cell.

Indeed, when the first cell receives the serial, it proceeds to read its first byte, and depending on its value ($1$, $2$, $3$ or $4$), it sends the rest of the serial to the left, right, up or down adjacent cell.

if (msgType == 'S') {

// Read the serial

serial_length = read_serial(R[16 * 0 + 4 * x + y], buffer);

// Read the next move (first byte of the serial)

// (this function translates 1,2,3,4 to an LRUD move)

convert_move(buffer[0], &dx, &dy);

if (x + dx < 0 || x + dx > 3 || y + dy < 0 || y + dy > 3) {

// No adjacent cell here, we're out of the grid

printf("You lost your path already?\n");

exit(1);

}

// Send the rest of the serial to the adjacent cell

send_serial(Q[64 * x + 16 * y + 4 * (x + dx) + (y + dy)], buffer + 1, serial_length - 1);

}

When the next cell receives the serial, things get a bit more complicated: we’ll see why with the C, A and V message types. But fundamentally, it will also send the rest of the serial to a next adjacent cell. If a child process receives a 1-byte serial, it also sends a last Send serial message with serialLength = 0.

Probe child status

[msgType (1 byte)]

msgTypemust be'P'

This message is used by the master process to probe all children for their cell numbers. Upon reception of this message, a child process responds with a Probe response message.

This appears in the function probe_children_status, which sends a probe P to all children to check whether they are alive, but also to get their cell numbers and store them in a 16-byte state array. Hence, this function is periodically called during the master loop, but also called once when asked for verification (see V).

Probe response

[msgType (1 byte)] + [cellNumber (1 byte)]

msgTypemust be'R'cellNumbermust be in $\{ 0, \ldots, 15 \}$

This message is used by a child process to respond to the master’s Probe child status with their cell number.

The master process can consider one of their children to be dead if they do not answer with a Probe response within a certain timeout delay (30 seconds).

In the child loop:

// Probe child status

if (msgType == 'P') {

// Send cell number back to master

probe_response(S[16 * 1 + 4 * x + y], cell_number);

}

Send old cell number

[msgType (1 byte)] + [oldCellNumber (1 byte)]

msgTypemust be'C'oldCellNumbermust be in $\{ 1, \ldots, 15 \}$

This message is used by a child process to send back their old cell number in response to a Send serial message from an adjacent child process cell.

Indeed, when a child process sends the remaining serial (S) to another child process, here is what does the new cell:

if (msgType == 'S') {

// Received remaining serial

serial_length = read_serial(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y], buffer);

// Send old cell number back to adjacent cell

if (send_old_cell_number(Q[64 * x + 16 * y + 4 * (x + dx) + (y + dy)], cell_number) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

cell_number = 0;

// ...

}

The new cell becomes $0$, and sends its old cell number back to the previous cell, which does this:

if (msgType == 'C') {

// Change cell number

if (read(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y], &cell_number, 1) <= 0) {

printf("read error\n");

exit(-1);

}

if (cell_number <= 0 || cell_number > 15) {

printf("malformed data\n");

exit(-1);

}

// Acknowledge

if (acknowledge(Q[64 * x + 16 * y + 4 * (x + dx) + (y + dy)]) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

The previous cell sets its new cell number to the one sent by the next cell!

This is how we are able to move the cells. With this information in our possession, we could already start solving the puzzle…

Acknowledge

[msgType (1 byte)]

msgTypemust be'A'

This message is used by a child process to acknowledge they received a Send old cell number message. It is primarily useful for synchronization purposes: the new cell will not process the remaining part of the serial before it received this acknowledgement.

Ask master for verification

[msgType (1 byte)]

msgTypemust be'V'

Last but not least, this message is used by a child process once there are no more remaining moves in the serial to ask for the master process to verify the state of the grid. This is, as we saw earlier, what results in a win or a loss.

if (serial_length == 0) {

if (ask_master_for_verification(S[16 * 1 + 4 * x + y]) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

Upon reception of this message, the master process sends a Probe child status message to every children, reconstruct the state array and announce whether the user won or lost before killing every children.

if (msgType == 'V') {

// Child asked for verification

// Reprobe everyone and construct state matrix

memset(state, 0, 16);

probe_children_status(state);

// Check if instance is solved

for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++) {

for (int l = 0; l < 4; l++) {

if (state[4 * k + l] != 4 * k + l) {

goto bad_boy;

}

}

}

printf("That's pretty good!\n");

kill_children();

exit(0);

bad_boy:

printf("You failed really hard. At least you managed to survive...\n");

kill_children();

exit(1);

}

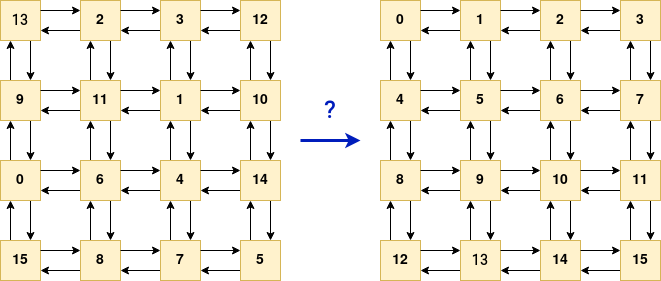

Puzzle state machine

Now that we have acquired a deeper understanding of the binary, we can try to summarize its inner workings schematically.

So… does it ring a bell?

If not, let me introduce you to the Fifteen Puzzle!

The Fifteen Puzzle is a sliding puzzle with a $4 \times 4$ grid that has 15 square tiles and one hole. Tiles are associated a number and can slide. When you slide a tile next to a hole, it fills this hole, but also of course creates a new hole.

The goal is to rearrange the tiles from $1$ to $15$. Depending on variants, the hole has to eventually sit in the top-left corner or the bottom-right corner. There are also variants where the goal is to unscramble a picture.

In our case, the hole is represented by the cell number $0$. When two cells swap numbers, it’s actually the second cell that fills the place of the old $0$ cell — this is how tiles slide.

In conclusion, the username is used to derive a random instance of a Fifteen Puzzle game, and the serial encodes which tile slides at each step. The goal is to solve the puzzle!

Writing a keygen

Now that we have all the pieces together, it’s time to write a keygen. Fortunately, there are plenty of Fifteen Puzzle solvers on the Internet in many languages, so it shouldn’t be too hard to come up with something.

I will not share my keygen because it’s dirty and embarassing. It basically just computes the initial state and then runs a slightly modified version of a C++ Fifteen Puzzle solver I shamelessly cloned and compiled. Modifications include:

- changing the goal matrix (most solvers put the hole at the bottom-right);

- outputting the solution in a format that is convenient for us, i.e. LRUD moves relatively to the hole’s position at each step.

Most Fifteen Puzzle solvers seem to use A* or IDA*. Some are faster than the others, and some are easier to modify than the others, so in a short-time competition context (which ECW is actually not really since it spans for two weeks…), finding an implementation that satisfies our needs doesn’t necessarily come right away.

You may also have noticed a little something that makes writing a “legitimate” keygen impossible.

It can be shown that among all the possible starting positions, only half of them actually are solvable. Indeed, it is easy to catch that the parity of the permutation of the cells plus the parity of the taxicab distance of the hole from its goal position (the top-left corner) is time invariant for a given instance of the puzzle. We can thus check if an instance is solvable by computing the invariant quantity and comparing it to $0$.

There’s actually a second, more subtle issue. Remember how the serial is converted? We have to provide a hexadecimal representation of a sequence of base 4 moves. This means that a hexadecimal character, like B, encodes two moves at once ($(3, 4)$). Consequently, we have no choice but to provide a solution of even length. Again, having a solution of even length is equivalent to the number of inversions in the permutation being even.

Therefore, for a given username, which we suppose uniformly randomly generated, there’s only a $\frac{1}{4}$ probability that we can find a corresponding valid serial.

Some example runs:

$ python keygen.py Username1

Odd-length solution

$ python keygen.py Username2

Serial: 2728F729973360972973608

$ python keygen.py Username3

Serial: F68CD60D708D970962720D8FD982

$ python keygen.py Username4

Not solvable

$ python keygen.py Username5

Serial: 30A73D58A7C8F6A7F28F6602

$ python keygen.py Username6

Not solvable

$ python keygen.py abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

Odd-length solution

$ ./pipedream

Enter username: Username2

Enter serial: 2728F729973360972973608

That's pretty good!

[1] 3174889 killed ./pipedream

Victory!

Against the remote

Final stretch: defeat the remote and get the flag.

First step

We connect to the remote and are greeted with a “gentle” task.

[+] Hello there. Did you manage to find your way?

[+] Just a quick sanity check, I'll start with something gentle.

[+] I will give you 5 usernames, and each time you will have to send me a valid serial in less than 15 seconds.

[?] Give me a valid serial for the user 'boHehgOO22'.

>>>

Solving the fifteen puzzle in fifteen seconds should be largely enough. We have to do this 5 times.

Thanksfully, it seems that the generated usernames are all “valid” (the grids they generate are all solvable, and their solutions are always of even length).

Nothing too special here:

from pwn import *

import keygen, crctools

r = remote('localhost', 42000)

for k in range(5):

c = r.recvuntil(b">>> ")

print(c.decode())

user = c.split(b"user '")[1].split(b"'")[0].decode()

serial = keygen.keygen(user)

r.sendline(serial.encode())

r.interactive()

Let’s run it:

[+] Opening connection to localhost on port 42000: Done

[+] Hello there. Did you manage to find your way?

[+] Just a quick sanity check, I'll start with something gentle.

[+] I will give you 5 usernames, and each time you will have to send me a valid serial in less than 15 seconds.

[?] Give me a valid serial for the user 'E8kMpXJaqY'.

>>>

Serial: C8DC9D7260973297336720DA8D60

[+] Correct!

[?] Give me a valid serial for the user 'NtL4fPJID6'.

>>>

Serial: 0D63CD668F0D5A30D58267C88

[+] Correct!

[?] Give me a valid serial for the user 'PpGRKyBz9F'.

>>>

Serial: DA9C257F20A7F6A3D9C358C2A

[+] Correct!

[?] Give me a valid serial for the user 'be1VpeDkA2'.

>>>

Serial: 95CD8095C27CA3D9DA27CA0D632

[+] Correct!

[?] Give me a valid serial for the user 'EqM8S0yWey'.

>>>

Serial: 98F68D7367263267CA3DC8D60A

[+] Correct!

[+] Easy, right?

[+] Now I will ask you to give me 1337 usernames, and a valid serial for each one.

[+] Every username should be distinct, [0-9A-Za-z]+ and start with '6FnUdNnG99'.

[+] You have 10 seconds for the whole thing. Good luck!

A little twist

There’s a second step… 1337 usernames in 10 seconds? I don’t know if there’s an implementation out there that can go that fast on an average computer. My keygen already takes a few seconds for each username.

There must be a way to entirely circumvent this step. We know we have a new degree of freedom: we can choose arbitrary usernames (as long as they start with the given prefix).

Of course, the idea is that there is a weakness in this hospital’s authentication system (yeah, don’t forget we’re trying to hack into a backdoor to arrest evil hacktivists…).

Since the initial grid is derived from a PRNG seeded with 32 bits of entropy, only $\frac{2^{32}}{16!} \approx 0.02\%$ of the initial grid space is covered. More particularly, it is trivial to generate many collisions because the initial grid only depends on the value of the username’s CRC32.

In order to generate CRC collisions, I used this Python tool, which I modified a bit to integrate better to my script. The reverse_callback function takes a prefix CRC and allows to find 4-byte, 5-byte and 6-byte alphanumeric patches to match a target CRC. Obviously, it won’t yield 1337 patches at once, but it doesn’t matter; we can add random junk to our string and ask for new patches until we reach 1337 usernames that all give the same CRC.

For the target CRC, we can simply choose the CRC of the last username of step 1. This way, we don’t even have to solve another instance of the puzzle: we already know a valid serial.

Here’s the last part of our solve script:

from binascii import crc32

import crctools

# [...]

c = r.recvuntil(b"Good luck!")

print(c.decode())

prefix = c.split(b"start with '")[1].split(b"'")[0].decode()

prefix_crc = crc32(prefix.encode())

target_crc = crc32(user.encode()) # user is the last username from step1

interesting = []

while len(interesting) < 1337:

out = crctools.reverse_callback(target_crc, prefix_crc)

interesting += [prefix + x for x in out]

prefix += "zboub"

prefix_crc = crc32(prefix.encode())

print("Generated 1337 fitting usernames with same serial")

interesting = interesting[:1337]

for i, x in enumerate(interesting):

assert crc32(x.encode()) == target_crc

r.recv(4096)

r.sendline(x.encode())

r.recv(4096)

r.sendline(serial.encode())

r.interactive()

r.close()

And what the end looks like:

[+] Now I will ask you to give me 1337 usernames, and a valid serial for each one.

[+] Every username should be distinct, [0-9A-Za-z]+ and start with '6FnUdNnG99'.

[+] You have 10 seconds for the whole thing. Good luck!

Generated 1337 fitting usernames with same serial

[+] You really found your path... congrats!

[+] I was told you might find this useful: ECW{83b772c13bb412191875ea890fc82b90d2a9a7a7}

Note: during the ECW, on the remote CTF infrastructure, the timeout for the second step was revised to 90 seconds because of network delay.

Conclusion

With Pipe Dream, my objective was to design a reverse engineering challenge that relied on system features (fork, pipes, select…) to implement a logic puzzle, while remaining as pure as possible.

I know there exist other challenges of this kind and that Pipe Dream is not necessarily the most innovative, but I still hope this was an enjoyable and fresh experience for most people who gave it a chance.

My only regret with this challenge is that it all comes down to an existing puzzle for which there already are plenty of solvers out there. But at the same time, I didn’t want it to be too difficult, especially for a time-limited CTF, hence why I implemented a well-known game that people could recognize.

Full source code

If you are interested in it, here is the full source code of pipedream.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <sys/select.h>

// #define DEBUG

#define LEFT 1

#define RIGHT 2

#define UP 3

#define DOWN 4

static unsigned int next = 1;

static pid_t pgid;

static unsigned char cell_number;

static int P[256] = { 0 }; // P[64 * i + 16 * j + 4 * k + l] -> fd of reading end of pipe from (i, j) to (k, l)

static int Q[256] = { 0 }; // Q[64 * i + 16 * j + 4 * k + l] -> fd of writing end of pipe from (i, j) to (k, l)

static int R[32] = { 0 }; // R[16 * z + 4 * i + j] -> fd of reading end of pipe from master to (i, j) if z = 0, or from (i, j) to master if z = 1

static int S[32] = { 0 }; // S[16 * z + 4 * i + j] -> fd of writing end of pipe from master to (i, j) if z = 0, or from (i, j) to master if z = 1

void kill_children() {

if (killpg(pgid, SIGKILL) == -1) {

printf("killpg failed\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

void handle_int(int sig) {

kill_children();

exit(1);

}

unsigned char my_rand(unsigned int modulus) {

next = next * 1103515245 + 12345;

return (unsigned int)(next % modulus);

}

void my_srand(unsigned int seed) {

next = seed;

}

unsigned int crc32_for_byte(unsigned int r) {

for(int j = 0; j < 8; ++j)

r = (r & 1 ? 0 : (unsigned int)0xEDB88320L) ^ r >> 1;

return r ^ (unsigned int)0xFF000000L;

}

void crc32(const void * data, size_t n_bytes, unsigned int * crc) {

static unsigned int table[0x100];

if(!*table)

for(size_t i = 0; i < 0x100; ++i)

table[i] = crc32_for_byte(i);

for(size_t i = 0; i < n_bytes; ++i)

*crc = table[(unsigned char)*crc ^ ((unsigned char *)data)[i]] ^ *crc >> 8;

}

void hex_to_base4(char * buffer, char * out_buffer) {

int i = 0;

unsigned char j = 0;

while (buffer[i]) {

if (buffer[i] >= '0' && buffer[i] <= '9') {

j = buffer[i] - '0';

} else if (buffer[i] >= 'A' && buffer[i] <= 'F') {

j = buffer[i] - 'A' + 10;

} else {

printf("Not even close. Bye!\n");

kill_children();

exit(1);

}

out_buffer[2 * i] = 1 + (j / 4);

out_buffer[2 * i + 1] = 1 + (j % 4);

i++;

}

out_buffer[2 * i] = 0;

}

void fisher_yates_shuffle(unsigned char permutation[], unsigned int length) {

unsigned char tmp;

unsigned int j;

for (int i = 0; i < length - 1; i++) {

tmp = permutation[i];

j = i + my_rand(length - i);

permutation[i] = permutation[j];

permutation[j] = tmp;

}

}

void initialize_pipes() {

int pipefdbuf[2];

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

// Adjacent pipes

for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++) {

for (int l = 0; l < 4; l++) {

if (i == k && abs(j - l) == 1 || j == l && abs(i - k) == 1) {

if (pipe(pipefdbuf) != 0) {

printf("pipe failed\n");

exit(-1);

}

P[64 * i + 16 * j + 4 * k + l] = pipefdbuf[0];

Q[64 * i + 16 * j + 4 * k + l] = pipefdbuf[1];

}

}

}

// Master <-> child pipes

for (int z = 0; z < 2; z++) {

if (pipe(pipefdbuf) != 0) {

printf("pipe failed\n");

exit(-1);

}

R[16 * z + 4 * i + j] = pipefdbuf[0];

S[16 * z + 4 * i + j] = pipefdbuf[1];

}

}

}

}

void convert_move(unsigned char move, int * dx, int * dy) {

switch (move) {

case LEFT: *dx = 0; *dy = -1; break;

case RIGHT: *dx = 0; *dy = 1; break;

case UP: *dx = -1; *dy = 0; break;

case DOWN: *dx = 1; *dy = 0; break;

default:

printf("malformed data\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

unsigned char read_header(int fd) {

unsigned char msgType;

if (read(fd, &msgType, 1) <= 0) {

printf("read error\n");

exit(-1);

}

return msgType;

}

unsigned char read_header_master(int fd) {

unsigned char msgType;

if (read(fd, &msgType, 1) <= 0) {

printf("read error\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

}

return msgType;

}

ssize_t send_serial(int fd, unsigned char serial[], unsigned int serial_length) {

ssize_t retval;

unsigned char * buffer = malloc(3 + serial_length);

buffer[0] = 'S';

buffer[1] = serial_length & 0xFF;

buffer[2] = (serial_length >> 8) & 0xFF;

memcpy(buffer + 3, serial, serial_length);

retval = write(fd, buffer, 3 + serial_length);

free(buffer);

return retval;

}

unsigned int read_serial(int fd, unsigned char * buffer) {

unsigned char size[2];

unsigned int serial_length;

if (read(fd, size, 2) == -1) {

printf("read error\n");

exit(-1);

}

serial_length = size[0] | (size[1] << 8);

if (read(fd, buffer, serial_length) == -1) {

printf("read error\n");

exit(-1);

}

return serial_length;

}

ssize_t probe_child_status(int fd) {

return write(fd, "P", 1);

}

ssize_t probe_response(int fd, unsigned char cellNumber) {

ssize_t retval;

unsigned char buffer[2];

buffer[0] = 'R';

buffer[1] = cellNumber;

return write(fd, buffer, 2);

}

ssize_t send_old_cell_number(int fd, unsigned char oldCellNumber) {

ssize_t retval;

unsigned char buffer[2];

buffer[0] = 'C';

buffer[1] = oldCellNumber;

return write(fd, buffer, 2);

}

ssize_t acknowledge(int fd) {

return write(fd, "A", 1);

}

ssize_t ask_master_for_verification(int fd) {

return write(fd, "V", 1);

}

void probe_children_status(unsigned char state[]) {

// Send probe 'P' to all children to check if they are alive

// If state is not NULL, sequentially construct the state matrix from their cell numbers

fd_set probed_children_read_fds;

unsigned char probed_cell_number;

// Also have a timeout on getting a child's probe response because there's a chance they killed themselves

struct timeval timeout;

timeout.tv_sec = 1; timeout.tv_usec = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++) {

for (int l = 0; l < 4; l++) {

if (probe_child_status(S[16 * 0 + 4 * k + l]) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

}

FD_ZERO(&probed_children_read_fds);

FD_SET(R[16 * 1 + 4 * k + l], &probed_children_read_fds);

switch (select(R[16 * 1 + 4 * k + l] + 1, &probed_children_read_fds, NULL, NULL, &timeout)) {

case -1:

printf("select error\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

case 0:

printf("I lost my child :(\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

default:

break;

}

if (read_header_master(R[16 * 1 + 4 * k + l]) != 'R') {

printf("malformed data\n");

exit(-1);

}

if (read(R[16 * 1 + 4 * k + l], &probed_cell_number, 1) <= 0) {

printf("read error\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

}

if (state == NULL) {

continue;

}

if (probed_cell_number >= 0 && probed_cell_number < 16) {

state[4 * k + l] = probed_cell_number;

} else {

printf("malformed data\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

}

}

}

}

void child_loop(int x, int y) {

fd_set read_fds;

int maxfd, dx, dy;

char buffer[2048];

ssize_t bytes_read;

unsigned int serial_length;

unsigned char msgType;

struct timeval timeout, timeout_long;

timeout.tv_sec = 1; timeout.tv_usec = 0;

timeout_long.tv_sec = 30; timeout_long.tv_usec = 0;

while (1) {

// Wait for data from an adjacent pipe or master

FD_ZERO(&read_fds);

maxfd = 0;

for (dx = -1; dx <= 1; dx++) {

for (dy = -1; dy <= 1; dy++) {

if ((dx && dy) || (dx == 0 && dy == 0)) continue;

if (x + dx >= 0 && x + dx <= 3 && y + dy >= 0 && y + dy <= 3) {

FD_SET(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y], &read_fds);

if (P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y] > maxfd)

maxfd = P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y];

}

}

}

FD_SET(R[16 * 0 + 4 * x + y], &read_fds);

if (R[16 * 0 + 4 * x + y] > maxfd)

maxfd = R[16 * 0 + 4 * x + y];

switch (select(maxfd + 1, &read_fds, NULL, NULL, &timeout_long)) {

case -1:

printf("select error\n");

exit(-1);

case 0:

// Long timeout, consider master as long dead. Silently exit.

exit(-1);

default:

break;

}

// Received from master

if (FD_ISSET(R[16 * 0 + 4 * x + y], &read_fds)) {

msgType = read_header(R[16 * 0 + 4 * x + y]);

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[%d,%d] Received from master: %c\n", x, y, msgType);

#endif

if (msgType == 'P') {

// Probe child status

// Send cell number back to master

if (probe_response(S[16 * 1 + 4 * x + y], cell_number) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

} else if (msgType == 'S') {

// Received the whole serial (starting cell), send it to next cell

serial_length = read_serial(R[16 * 0 + 4 * x + y], buffer);

#ifdef DEBUG

debug_print_serial(buffer, serial_length);

#endif

convert_move(buffer[0], &dx, &dy);

if (x + dx < 0 || x + dx > 3 || y + dy < 0 || y + dy > 3) {

printf("You lost your path already?\n");

exit(1);

}

if (send_serial(Q[64 * x + 16 * y + 4 * (x + dx) + (y + dy)], buffer + 1, serial_length - 1) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

} else {

printf("malformed data\n");

exit(-1);

}

} else {

// Find which adjacent cell sent the remaining serial

for (dx = -1; dx <= 1; dx++) {

for (dy = -1; dy <= 1; dy++) {

if ((dx && dy) || (dx == 0 && dy == 0)) continue;

if (x + dx >= 0 && x + dx <= 3 && y + dy >= 0 && y + dy <= 3) {

if (FD_ISSET(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y], &read_fds)) {

goto found_adjacent_cell;

}

}

}

}

found_adjacent_cell:

msgType = read_header(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y]);

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[%d,%d] Received from adjacent cell (%d, %d): %c\n", x, y, x + dx, y + dy, msgType);

#endif

if (msgType == 'C') {

// Change cell number

if (read(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y], &cell_number, 1) <= 0) {

printf("read error\n");

exit(-1);

}

if (cell_number <= 0 || cell_number > 15) {

printf("malformed data\n");

exit(-1);

}

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[%d,%d] My new cell number is %d\n", x, y, (int)cell_number);

#endif

// Acknowledge

if (acknowledge(Q[64 * x + 16 * y + 4 * (x + dx) + (y + dy)]) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

};

} else if (msgType == 'S') {

// Received remaining serial

serial_length = read_serial(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y], buffer);

#ifdef DEBUG

debug_print_serial(buffer, serial_length);

#endif

// Send old cell number back to adjacent cell

if (send_old_cell_number(Q[64 * x + 16 * y + 4 * (x + dx) + (y + dy)], cell_number) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

// We are now the hole

cell_number = 0;

// Wait for acknowledgement to pursue

fd_set adjacent_cell_read_fds;

FD_ZERO(&adjacent_cell_read_fds);

FD_SET(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y], &adjacent_cell_read_fds);

switch (select(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y] + 1, &adjacent_cell_read_fds, NULL, NULL, &timeout)) {

case -1:

printf("select error\n");

exit(-1);

case 0:

printf("I lost my brother... why bother anymore?\n");

exit(-1);

default:

break;

}

msgType = read_header(P[64 * (x + dx) + 16 * (y + dy) + 4 * x + y]);

if (msgType != 'A') {

printf("malformed data\n");

exit(-1);

}

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("[%d,%d] Received ack from (%d, %d)\n", x, y, x + dx, y + dy);

#endif

// If no more moves (null serial length), ask master for verification

if (serial_length == 0) {

if (ask_master_for_verification(S[16 * 1 + 4 * x + y]) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

} else {

// Send remaining serial to next cell

convert_move(buffer[0], &dx, &dy);

if (x + dx < 0 || x + dx > 3 || y + dy < 0 || y + dy > 3) {

printf("You lost your path and fell into lava. It hurts and you die.\n");

exit(1);

}

if (send_serial(Q[64 * x + 16 * y + 4 * (x + dx) + (y + dy)], buffer + 1, serial_length - 1) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

} else {

printf("malformed data\n");

exit(-1);

}

}

}

}

void master_loop() {

unsigned char msgType;

int maxfd;

fd_set read_fds;

unsigned char state[16];

struct timeval timeout, timeout_long;

timeout.tv_sec = 1; timeout.tv_usec = 0;

while (1) {

// Periodically probe children status

probe_children_status(NULL);

// Wait for data from any child

FD_ZERO(&read_fds);

maxfd = 0;

int i, j;

for (i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

FD_SET(R[16 * 1 + 4 * i + j], &read_fds);

if (R[16 * 1 + 4 * i + j] > maxfd)

maxfd = R[16 * 1 + 4 * i + j];

}

}

switch (select(maxfd + 1, &read_fds, NULL, NULL, &timeout)) {

case -1:

printf("select error\n");

exit(-1);

case 0:

// Timeout: no data available, just loop

break;

default:

// Data available from a child

goto data_available_from_child;

}

continue;

data_available_from_child:

// Find child that sent data

for (i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

if (FD_ISSET(R[16 * 1 + 4 * i + j], &read_fds)) {

goto found_child;

}

}

}

found_child:

msgType = read_header_master(R[16 * 1 + 4 * i + j]);

if (msgType == 'V') {

// Child asked for verification

// Reprobe everyone and construct state matrix

memset(state, 0, 16);

probe_children_status(state);

#ifdef DEBUG

// Display board state (debug)

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

printf("%d ", (int)state[4 * i + j]);

}

printf("\n");

}

printf("\n");

#endif

// Check if instance is solved

for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++) {

for (int l = 0; l < 4; l++) {

if (state[4 * k + l] != 4 * k + l) {

goto bad_boy;

}

}

}

printf("That's pretty good!\n");

kill_children();

exit(0);

bad_boy:

printf("You failed really hard. At least you managed to survive...\n");

kill_children();

exit(1);

} else {

printf("malformed data\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

}

}

}

#ifdef DEBUG

void debug_print_serial(unsigned char * buffer, unsigned int serial_length) {

printf("Serial : ");

for (int i = 0; i < serial_length; i++) {

printf("%u ", (unsigned int)buffer[i]);

}

printf("\n");

}

#endif

void main(int argc, char * argv[]) {

unsigned char msgType;

char username[512];

unsigned int username_crc = 0;

char hex_serial[512];

char serial[2048];

unsigned int serial_length;

unsigned char initial_state[] = { 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 };

printf("Enter username: ");

scanf("%511s", username);

crc32(username, strlen(username), &username_crc);

my_srand(username_crc);

fisher_yates_shuffle(initial_state, 16);

#ifdef DEBUG

// Display initial board state (debug)

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

printf("%d ", (int)initial_state[4 * i + j]);

}

printf("\n");

}

printf("\n");

#endif

initialize_pipes();

pid_t pid;

int x, y;

for (x = 0; x < 4; x++) {

for (y = 0; y < 4; y++) {

if ((pid = fork()) == -1) {

printf("fork failed\n");

exit(-1);

}

if (pid == 0) {

goto out_fork_loop;

}

}

}

out_fork_loop:

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process (x, y)

cell_number = initial_state[4 * x + y];

child_loop(x, y);

} else {

// Master process

setsid(); // Make the master process the group leader if it's not already

pgid = getpgid(pid); // Process group of child processes

// Cleanly kill children on CTRL+C

struct sigaction act;

act.sa_handler = handle_int;

sigaction(SIGINT, &act, NULL);

printf("Enter serial: ");

scanf("%511s", hex_serial);

hex_to_base4(hex_serial, serial);

serial_length = 2 * strlen(hex_serial);

if (serial_length < 1) {

printf("Serial is too short!\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

}

/*

printf("Base4 conversion result: ");

for (int i = 0; i < serial_length; i++) {

printf("%d ", (int)serial[i]);

}

printf("\n");

*/

// Find the "hole" process (cell_number=0)

int i, j;

for (i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

if (initial_state[4 * i + j] == 0) {

goto found_hole;

}

}

}

found_hole:

// Send the serial to the hole process (i, j)

if (send_serial(S[16 * 0 + 4 * i + j], serial, serial_length) == -1) {

printf("write error\n");

kill_children();

exit(-1);

}

master_loop();

}

}